Bisecting as a troubleshooting technique, and how Git makes it even better

If you are more of a visual learner, I have a companion video covering general points in this article:

I have this method for finding a bug when it is showing itself to be particularly tricky to locate or reproduce. I have called it the “binary search method” for a while now, because I never bothered to come up with an actually good name and it is described quite well by this one, but only if you know what a binary search is.

A binary search can be simplified to cutting a sorted list in half and seeing if the middle is what you were looking for, or if it is greater or less than what you are looking for. You keep repeating this process, chopping in half what you just chopped in half, until you get to what you were looking for. Feel free to look it up for a more accurate and thorough description, but I think this will suffice for this article.

Before I move on, if you prefer to jump right to code examples I have created an Example Repository with instructions in the readme for trying it out. The rest of this article will be my longform explanation about my debugging techniques, git bisect, and an example of when it is useful. I’ve also got something really cool at the end of the article.

The poorly named “binary search” method of finding a bug

So what I do is pretty simple, yet extremely effective when I’ve exhausted the “easy” ways of finding a bug. I put a bunch of logs in my code, and then I delete/comment out about half the code. I run my code, check the logs, and see if the bug goes away. Sometimes this is as easy as deleting the bottom half of a page, or removing a whole import of a file. Sometimes it takes a little more finesse, because the code might not be written into small enough units/functions.

I am not intending to say I pioneered this method, as I’m sure many others have thought of it. I do introduce it to fellow programmers quite often, though, so I wanted to describe it briefly for anyone not familiar. Now that you have the background, let us move on to the real subject of the article.

Discovering the method in the wild

While I was doing my nightly twitter cruise, I found this interesting tweet from Dan Abramov:

Bisecting is one of the most effective ways to debug problems. Therefore, to onboard someone to a codebase you need to teach them to bisect problems in it. You need to know the layers and their order so you can cut them in half and see where exactly the assumptions failed.

— Dan Abramov (@dan_abramov) April 8, 2020

It caught my attention, and even though I wasn’t familiar with the phrase “bisecting” in code, I immediately thought of my binary search bug-finding method from the context. As I read through the replies, I found this followup tweet that verified my suspicion and gave me a mindblown moment:

Think of a binary search but for debugging. You can bisect commits to find a bug by finding a commit where it doesn't repro. Check the commit halfway between master and that one. Depending on whether or not it repros, check the halfway point between those commits, etc.

— Royi Hagigi (@rhagigi) April 8, 2020

Wow. To not only realize this is a regular practice but also to find other people using the same terminology to explain it was surreal. Then I saw a bunch of various replies talking about git bisect. I had a hard time going to sleep because I was now curious if git had some automated way to do this and my mind started imagining what that looked like.

First thing in the morning I made a repository for trying it out and this is how it turned out.

Introduction to the Example Repository

I have been rereading Martin Fowler’s book, Refactoring, since the second edition came out with JavaScript examples. This was really cool of him to do; it helps the content to be more approachable to newer developers, since JavaScript has been on the rise and very popular for some years now (it remains at the top of the Stack Overflow survey at least since 2015, but that is obviously not the only metric to follow).

This time through the book I’ve been following along with the examples and running my code with jest snapshots after each refactoring step. This seemed like a solid example scenario to test git bisecting, and a good balance between realistic and simple for example purposes.

Each commit is prefixed with “refactor”, the type of refactor (from the book), and what was refactored, if possible. Like so:

refactor: Extract Function -> amountForOften a refactor needs to consist of multiple steps and commits. In these cases I use the term prev to say “this is part of the previous refactor”, like so:

refactor: prev -> renaming variablesAt the end of all of these steps, when a refactor is complete and working (hopefully passing tests), you would rebase all these commits into a single refactor commit. For the time being, you want a lot of small steps to be able to isolate any issues you introduce. The perfect setup for a git bisect example.

The Bug

On commit c12489 I purposefully introduced a bug during the refactor that changes the final calculation. Here is the commit message:

commit c12489cca6cffbee4998bd3c45bfb36a387fb128

Author: Jimmy DC <jimmydalecleveland@gmail.com>

Date: Wed Apr 8 08:48:23 2020 -0600

refactor: Extract Function -> volumeCreditsFor()

!! I introduced a bug here !!I have tried to make this a subtle bug, so I’ll show you the output if we just run the program.

# Here's the original correct output:

> $ node index.js

'Statement for BigCo\n' +

' Hamlet: $650.00 (55 seats)\n' +

' As You Like It: $580.00 (35 seats)\n' +

' Othello: $500.00 (40 seats)\n' +

'Amount owed is $1,730.00\n' +

'You earned 47 credits\n'# Here is the output with the bug:

> $ node index.js

'Statement for BigCo\n' +

' Hamlet: $650.00 (55 seats)\n' +

' As You Like It: $580.00 (35 seats)\n' +

' Othello: $500.00 (40 seats)\n' +

'Amount owed is $1,730.00\n' +

'You earned 137 credits\n'It honestly would be easy to miss this bug without a test, since all that has changed is the credits going from “47” to “137”. During the refactor, I “accidentally” messed up the credits calculation math. We are pretending that I didn’t notice that, and continued making refactor commits.

Now, multiple commits later, we realize we have a bug. This is the time for bisect to shine!

Using git bisect to find our bug

The purpose of git bisect is to find the origin of a bug in your git history by starting with a known bad/new commit, which is the earliest point we know a bug exists, and a good/old commit which is the earliest point we know the bug did not exist. Git will then “bisect” or, as I described it earlier with the binary search, chop the history in half and see if the bug exists. I’m using bug pretty generally here, it could be a performance regression or any unwanted behavior. So we’ll start by running the associated commands with that criteria.

You’ll start by running:

git bisect startYou then tell it the bad commit, which is usually the commit you are currently on. If it is, enter:

git bisect badThen we will tell git what commit worked properly. I typically look through the git logs for the origin of the feature commit that is now broken and use that as a starting point. If you want, you can narrow it down further, of course. copy that commit hash and run:

git bisect good 7ace8After a good and bad commit have been declared, git will checkout the commit halfway between the two. You’ll see some output like this:

Bisecting: 5 revisions left to test after this (roughly 3 steps)

[3f09766487e142c2d16e26268244b59e0ec63c61] refactor: Change Function DeclarationAt this point, you should run the code and see if it breaks. For my example you can simply run:

node index.jsWhich will output:

'Statement for BigCo\n' +

' Hamlet: $650.00 (55 seats)\n' +

' As You Like It: $580.00 (35 seats)\n' +

' Othello: $500.00 (40 seats)\n' +

'Amount owed is $1,730.00\n' +

'You earned 47 credits\n'This is a good commit, the code works as expected because “47 credits” was in the output. We’ll label this commit as a good one:

git bisect goodGit will automatically check out the next commit between the commit we just labeled as good, and our starting point bad commit:

Bisecting: 2 revisions left to test after this (roughly 2 steps)

[c12489cca6cffbee4998bd3c45bfb36a387fb128] refactor: Extract Function -> volumeCreditsFor()When we run node index.js on this commit, we get a bad commit output:

'Statement for BigCo\n' +

' Hamlet: $650.00 (55 seats)\n' +

' As You Like It: $580.00 (35 seats)\n' +

' Othello: $500.00 (40 seats)\n' +

'Amount owed is $1,730.00\n' +

'You earned 137 credits\n'Since we got the wrong number, “137 credits”, we’ll label this as a bad commit:

git bisect badWe’ll continue this process until we reach the end. Git will checkout a new commit, we’ll tell it if it is good or bad, and it’ll split the list of remaining commits to check in half. During any point in this process you can use see all the commits you’ve checked and how you’ve labeled them by running:

git bisect log

# bad: [99f5d6cff41e34be56b87ca833d23dfd87dbb4e1] Add simple readme

git bisect bad 99f5d6cff41e34be56b87ca833d23dfd87dbb4e1

# good: [7ace8bed2d59a8189e939a21c5651ec52293ecf7] initial working commit with test

git bisect good 7ace8bed2d59a8189e939a21c5651ec52293ecf7

# good: [3f09766487e142c2d16e26268244b59e0ec63c61] refactor: Change Function Declaration

git bisect good 3f09766487e142c2d16e26268244b59e0ec63c61The standard git log will also include the “good” and “bad” information alongside the commit label.

Eventually you will reach the end, and git will output something like this:

c12489cca6cffbee4998bd3c45bfb36a387fb128 is the first bad commit

commit c12489cca6cffbee4998bd3c45bfb36a387fb128

Author: Jimmy DC <jimmydalecleveland@gmail.com>

Date: Wed Apr 8 08:48:23 2020 -0600

refactor: Extract Function -> volumeCreditsFor()

!! I introduced a bug here !!

:100644 100644 50a8a5efa226292347b33cd806d52fbd70010f95 6ee577b57c0d6f3433c7ed10b0b77a07d54d158b M invoicePrinter.js

bisect run successI left that extra little message in the commit so we could be sure that the bisect was correct in finding the origin of the bug. Pretty amazing, huh? Now if only we had a test in place to speed up this process and make it a little less error prone.

Creating a test for easier bisecting

Now I’ll add a test, like I should have before starting the refactor. I am very guilty of this in the real world as well, and you should seriously always have tests if you are refactoring all but the simplest of codebases. Besides the obvious benefits, it really lifts some anxiety from your shoulders when you have a thorough test suite around code you are changing. So let us make the simplest test!

Testing the output of this invoice function is a great scenario for an inline snapshot:

test("prints an invoice", () => {

const firstInvoice = invoicePrinter(invoices[0], plays);

expect(firstInvoice).toMatchInlineSnapshot(`

"Statement for BigCo

Hamlet: $650.00 (55 seats)

As You Like It: $580.00 (35 seats)

Othello: $500.00 (40 seats)

Amount owed is $1,730.00

You earned 47 credits

"

`);

});Most of the time, snapshots are far too large to include inside my test file, but sometimes they are short enough that it can really help test readability by making them inline. Jest writes the output directly to your test file, I love it! With all of these amazing open source projects constantly coming out and being worked on, it really is a splendid time to be a developer.

We should do even more testing to further isolate potential bugs, but even this simple and easy to write test can take us a long way. Now we can open a new terminal and run:

npm t -- --watchThe extra -- is to pass additional flags to our test script, which you don’t have to do with yarn (yarn test --watch works fine). In this case we want to turn on watch mode so our tests run anytime our code changes. This is where the magic begins. If we start a git bisect at this point, each time a new commit is checked out, the tests will rerun and we’ll receive automatic feedback.

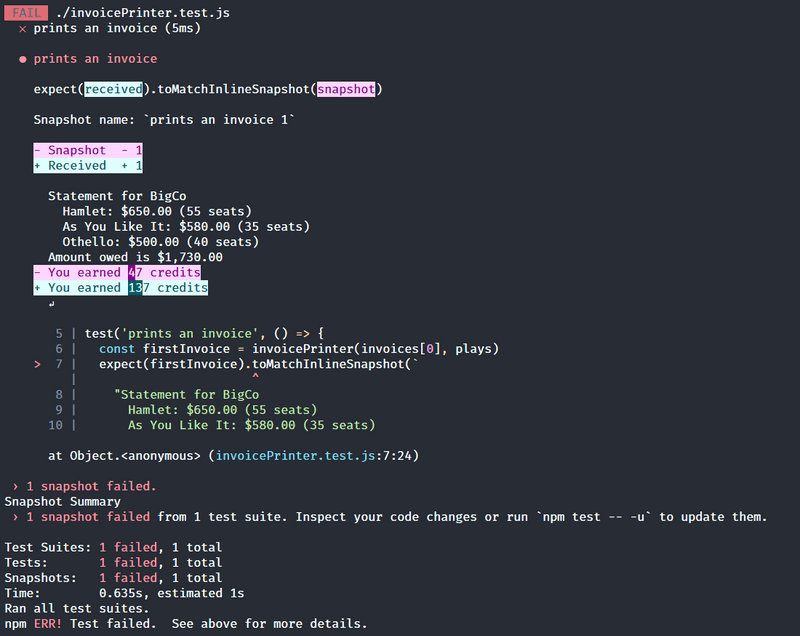

This is what it will look like when we find our first bad commit.

Note: This new format for snapshot diffing comes from Jest v25

It is mega cool and lovely to look upon. They really put some time and research into this decision and that is awesome. It does currently have a bug with emotion-jest, in case you encounter that, but they are working on it. (facebook/jest PR, emotion-js PR)

Now we don’t have to run node index.js every time, and it makes it less likely that we’ll miss a bad commit if we are doing this for a while and only partially paying attention. All we need to do is watch the tests and tell git whether it passed or failed, in the form of “bad” and “good”.

Or do we even have to do that…?

Automating bisect with a test script

I hope you stuck around, or scrolled to the bottom, for this part. It is just majestic, and I only learned of it today while writing this article. While I was going back and linking to the tweets, I found that more discussion had happened since I read the original and there was something very exciting waiting for me:

Wanna really cook with fire? You can write a bash script that will exit non-zero for a bad commit and automate this process further with `git bisect run test-script.sh`

— sMyle (@MylesBorins) February 12, 2018

Are you a node user? do you already have a test suite?

YOU CAN DO `git bisect run npm test`

This sounded too good to be true. Ok, so here’s how you do this. Start a bisect up, declare your initial good and bad, and then run something like this:

git bisect run npm testThe exit codes from the test passing or failing will tell git which commits are good or bad automatically. This is unbelievably cool, check this gif out to see the full run:

Conclusion

I know this was a long article, but it took me a while to discover how to use this feature properly, and to have some sort of example to try it out, so I’m hoping this is comprehensive enough for anyone who is brand new to the idea like I was.

In my project, I have the test included on the first commit, which makes the whole example somewhat unrealistic because how would a bug get into your code base if you are running tests in CI like you should be? Well this was just for demonstration, but it does not invalidate the usefulness of running tests with git bisect. If you find a bug, you can check out the commit where the code was working and write a test for it. If you do not commit it, but instead keep it in staging, you can run the full bisect process with the test running across every checked out commit.

I have actually tried this and it works pretty well. I’ve even used git bisect for a pesky bug on one of our Gatsby sites and it worked perfectly. All I had to do was run gatsby build each time to see if the build worked properly. If there are clientside actions that you don’t have tests for it might be a little more time consuming, but the bisecting process still shortcuts bug-finding drastically.

I’m excited to continue using and refining this process, and I am sure you will find some sweet uses for it as well.