A dive into transpiling through Webpack & Babel, plus reducing your bundle size

When I have researched this topic in the past I have been unsatisfied by the explanations and documentation surrounding the subject. I’m hoping to clarify some seemingly common confusion points, as well as showcase some minimal configurations to get immediate savings on your final output bundle.

We’ll also be taking a peek under the hood of what happens for some ES6+ transpiled syntax to demystify a few things. Just knowing a little bit of what is going on in the tools I use helps alleviate some of the anxiety I have about things that are “just magic” to me, and often gives me additional places to look during troubleshooting.

The setup

The source for the starting point of this article can be found here. This repository is a collection of minimal Webpack setups, each on their own branch, that I use as a reference for myself and explaining to others.

Note: Normally you wouldn’t push up your dist or distribution/public folder, but since this repo is for examples, I sometimes want to be able to reference the output without cloning down and building.

Let’s get into it

To begin with, we have a simple setup using Webpack and Babel to bundle and transpile a couple of small files that use syntax and methods from a few different ES versions after ES5. This is commonly referred to as ES2015+, or ES6+. You can reference the repo I linked above for the config files if you like, but I’m only going to show snippets of the pertinent code throughout this article.

From this point on I’ll be referring to the original, pre-transpiled code by the directory and filename: src/index.js. The transpiled output will be dist/main.js.

This is the file we wish to transpile. It has some examples of newer syntax, such as import, arrow functions, let and const, and the spread operator on an Object, as well as a few methods: Object.values and Array.includes. We’ll get into the reason why I make the distinctions between syntax and methods a little later. We’ll also get into the reason for the for loop later. You don’t need to understand everything about it right now, because I’ll be referring to lines from it as we break it down. It’s just here upfront for reference.

// src/index.js

import Wizard from "./Wizard";

const Ravalynn = new Wizard("Ravalynn", "Frost");

console.log(Ravalynn);

console.log("-------------------");

const component = () => {

let element = document.createElement("div");

const obj = { a: "alpha", b: "bravo" };

// ES7 Object spread test

const newObj = { ...obj, c: "charlie" };

console.log("ES7 Object spread example: newObj");

console.log(newObj);

// ES8 Object.values test

// Will not transpile without babel polyfills because it is a new method

console.log("-------------------");

console.log("ES8 Object.values example: Object.values(newObj)");

console.log(Object.values(newObj));

console.log("-------------------");

// ES Array.includes test

console.log("ES7 Array.includes example: ['a', 'b', 'c'].includes('b')");

console.log(["a", "b", "c"].includes("b"));

console.log("-------------------");

return element;

};

// Event queue block scoping test

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

setTimeout(function () {

console.log(i);

}, 1);

}

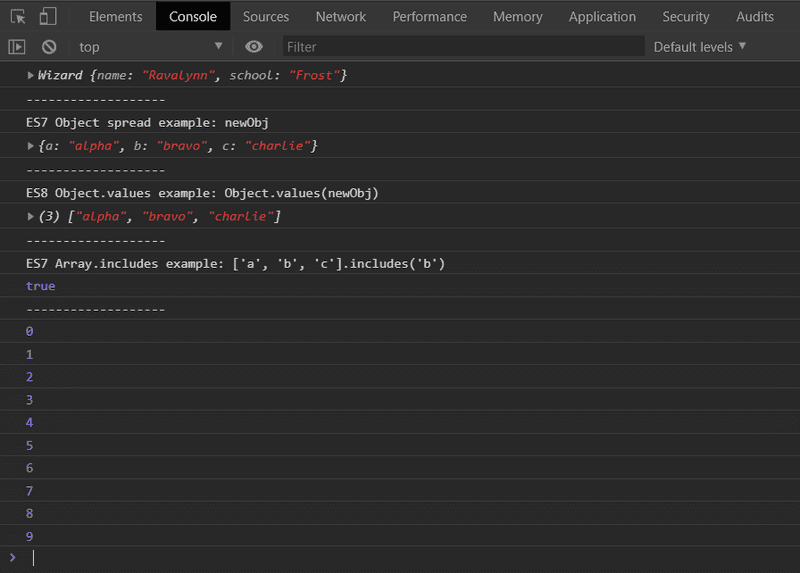

document.body.appendChild(component());After running this code through Babel, we can open it up in a browser and check out the console tab of devtools to see the output.

Everything runs as expected, with no errors. For people brand new to this world, this is where they might stop. But if you change the index.html to load the src/index.js, rather than the Babelified code, and remove the import statement and the associated invocation and log, you would see that the rest of the code works fine.

Note: If you are curious as to why we need to remove any imports to get it running in chrome, that is because Webpack is taking care of bundling all dependencies into a single file that the browser can load. Browsers don’t have a way of dealing with JavaScript imports currently.

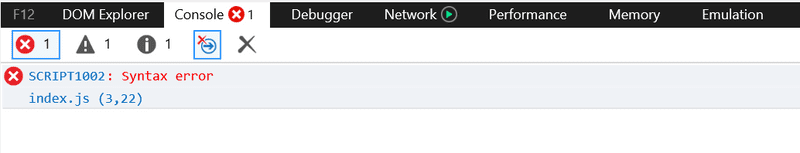

In this example I’m using Chrome 72, which supports all the previous code (import excluded, as it’s a special case). If we were to load this up in IE11, however, we’d see this:

It’s failing on line 3 when it encounters the => symbol. If you take a look at caniuse for ES6 arrow functions, you’ll see that IE11 does not support it, so that makes sense.

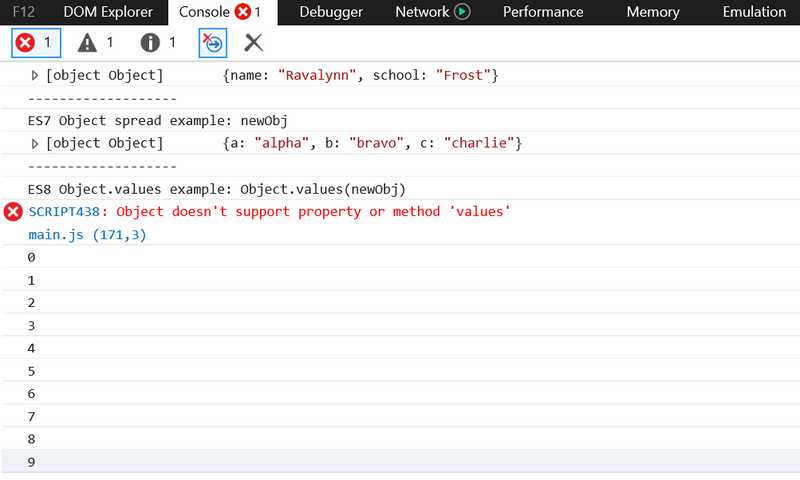

Let’s go back to the original, transpiled setup and see what happens in IE11.

It almost looks like we are back in business, with our import, arrow functions, Object spread, let and const all working… until we hit a snag on the Object.values part of our code.

You can see that IE11 does not know what the Object.values method is, as it throws this error when encountering it: Object doesn't support property or method 'values'.

This is the point where many become frustrated with Babel, saying something to the tune of “I thought preset-env was supposed to include everything from ES2015 and after”. I think it’s a fair assumption, but I have a bias since I’ve been there myself. The thing about present-env is that it includes all ES6+ syntax but not all the methods that have been added since ES5.

Let’s dive a little deeper

To explain this more clearly, we are going to look at some of the output from Babel. Let’s do a before and after of our Object.values problem child. Here’s the original.

// src/index.js

// ES8 Object.values test

// Will not be transpiled without polyfills since it's a new method

console.log(Object.values(newObj));And here is the relevant line in our dist/main.js.

// dist/main.js

console.log(Object.values(newObj));It’s the same as the original line, because it is a new method and that requires a “polyfill”, or backwards compatible replacement, in order to make it function correctly. preset-env is only for new syntax, and does not include polyfills for entirely new methods.

If we take a look at some new syntax, we’ll see that actual transpiling is being done by Babel.

// src/index.js

const obj = { a: "alpha", b: "bravo" };

// ES7 Object spread test

const newObj = { ...obj, c: "charlie" };// dist/main.js

var obj = {

a: "alpha",

b: "bravo",

}; // ES7 Object spread test

var newObj = _objectSpread({}, obj, {

c: "charlie",

});You’ll notice that the transpiled code has taken the spread syntax and replaced it with an _objectSpread function. If we look further up in this same file, we’ll find this:

function _objectSpread(target) {

for (var i = 1; i < arguments.length; i++) {

var source = arguments[i] != null ? arguments[i] : {};

var ownKeys = Object.keys(source);

if (typeof Object.getOwnPropertySymbols === "function") {

ownKeys = ownKeys.concat(

Object.getOwnPropertySymbols(source).filter(function (sym) {

return Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(source, sym).enumerable;

})

);

}

ownKeys.forEach(function (key) {

_defineProperty(target, key, source[key]);

});

}

return target;

}Babel has written a function to our output file that all browsers we wish to support can read.

Another example of this can be seen where block scoped variables (let and const) are involved, as long as they affect the result of the code. Let’s take a look at using let where the result is not affected, and then an example where it is.

In this first line of code you see that our before and after are almost identical. The let variable has simply been changed to var. The block scoping property of let in this instance doesn’t have any impact on our output that would require additional changes.

// src/index.js

let element = document.createElement("div");// dist/main.js

var element = document.createElement("div");But look at this next block of code. This is a common issue in Javascript that used to require the use of closures to get the desired output (I have a previous post covering Javascript closures basic concepts if you want more information about that). In this case we are wanting to log 0 through 9 as the loop progresses, but without the let variable we would get 10 logged 10 times.

This is because setTimeouts are placed on the event queue and can’t execute until the stack is clear again. The for loop will complete, and then each setTimeout’s callback will fire at once, referencing i which has been incremented to 10.

By using let we’ll block scope each instance of i that the corresponding setTimeout’s callback will reference. Check out the before and after.

// src/index.js

// Event queue block scoping test

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

setTimeout(function () {

console.log(i);

}, 1);

}// dist/main.js

var _loop = function _loop(i) {

setTimeout(function () {

console.log(i);

}, 1);

};

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

_loop(i);

}It seems that Babel has “intelligently” realized that our use of let will effect our desired output, so it creates a new function, _loop, to create a closure for each setTimeout so they can access i relative to when they are called.

Both of the previous examples were syntax additions to JavaScript so they will work without polyfills. The Object.values and Array.includes will not be transpiled to anything different, as they are not just syntax, but entirely new methods.

Why not just include the polyfills by default?

Sometimes this question comes up when someone’s code is failing on older browsers and they expected preset-env to include everything ES6+. The simple answer is that that would create a much larger file. I’ll throw out some relative numbers to this example to hopefully show how much larger that file can be. The unminified version of our dist/main.js is 196 lines, and the minified size is 2.55KiB. The unminified version, using polyfills, is over 9000 (9815 in this case). That’s 83.9 KiB minified!

That is obviously a TON of code for our end user to download. Any developers not wanting to support every browser under the sun would not want to be forced into this situation.

If you are using Webpack, you can add all polyfills by installing the @babel/polyfill package and updating your entry point in your webpack.config.js like so:

// webpack.config.js

module.exports = {

entry: ['@babel/polyfill', './src/index.js']

// ...Babel recommends you select each polyfill you need, rather than adding every polyfill that exists like the above example is doing, and now you know why.

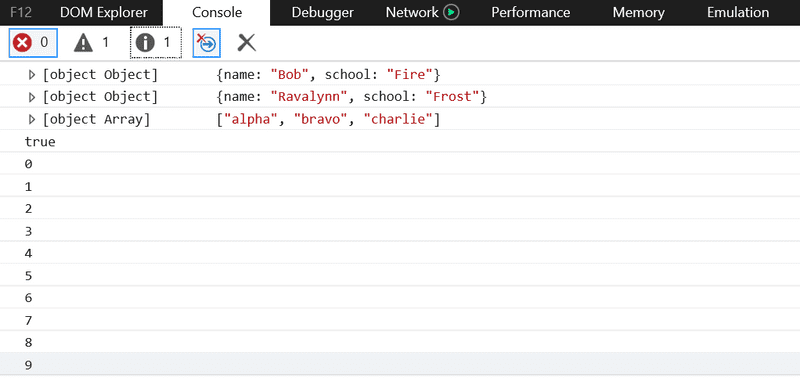

After adding polyfills, IE11 runs our code without errors.

Why not automatically add polyfills for methods my code actually uses?

In the .babelrc file, you can add the useBuiltIns option with the usage value to only add polyfills which your codebase uses. This is flagged as experimental in the Babel docs (as of March 2019). If you do this, do not add @babel/polyfill in your webpack entry point. You still need to have @babel/polyfill installed, but you shouldn’t require it anywhere in your codebase. Here’s an example of the .babelrc:

// .babelrc

{

"presets": [["@babel/preset-env", { "useBuiltIns": "usage" }]]

}The result of this build gives us a much smaller filesize, compared to adding all polyfills: 1512 lines unminified and 12.3 KiB minified.

That’s all for now, but in the next article I’ll be going into browserslist configurations and how you can narrow down which browsers you want your transpiling to support.